What are the matters of philosophy? How do they shape how philosophy is practiced, what kinds of knowledge it produces, and who counts as a philosopher? Feminist Philosophic Toys challenge what counts as serious philosophy by being seriously playful. The toys foreground the oral and the dialogic while reflecting on and committing to engaging materiality, record-keeping and record making. In doing so, the toys challenge the dominant form of philosophy and its mechanics of knowledge making as they offer an alternative way of doing philosophy that can be transformative for the next generation of feminist scholarship. The dialogic, embodied, and communal interaction with paper, with theory, and with others is meant as a practice of live theorization.

A room of one’s own (Wolfe 1929) and pieces of scrap paper (Lorde 2012, 116). The early morning time

(Morrison, 2003 (1993)) and the oppressor’s language (Rich 1984). These are the matters of

philosophy, hidden from purview and still invisible to those of privilege. They are what matters to

(feminist) philosophers and for (feminist) philosphy. That is, the kind of philosophy that is in

touch with reality. The dominant matters of Western philosophy, or its epistemic companions,

however, remain to be books and journal articles. The labor conditions of academia maintain the

dominance of the written text by devaluing, dismissing, or otherwise disregarding other forms of

knowledge making. Philosophy continues to be a “privileged discourse” to use bell hooks’ words, and

filled with “exclusive jargon,” which is often legitimized only within academic environments in the

global north.

We write as educators drawing on experiential knowledge of our own and observations of those around

us, especially our students. We both experience tensions and joys of growing up, living and working

at both margins and centers. In the context of paper and the page, the center affords a type of

dominant attention but the margins provide space for possibility. As women working in male-dominated

technological disciplines, it is no accident that we chose paper as our main medium. Caught between

disciplines and cultures and constantly struggling against norms and values that erase or actively

negate who we are, we both have first-hand experiences of questioning the validity of what we know

and our ways of knowing, too. Our individual pathways into this are markedly different, yet

strikingly similar. And, we see parallels in the expressions and experiences of our students,

especially those who find themselves pushed to the margins for one reason or another.

There is a big gap between understanding of design as a way of doing philosophy with liberatory

potential, and philosophy itself as embodied, situated, and experimental practice grounded in

specific social, historical moments with their own defining problems and dominant modes of art and

design education that simply bring philosophical text into the classroom. The latter risks merely

importing feminist philosophy into the classroom, rendering it as theoretical filter for what

students are experiencing or even worse appropriating into patriarchal structures of knowledge

making. This approach fails to foster thinking and imagination that is possible both with philosophy

and design.

What if we could facilitate meaningful engagement or serious play with the matters of feminist

philosophy? Can we conceive of educational materials collaboratively constructed by hand, in a

personal gesture of making that could cultivate a practice of live theorization in the spirit of

play and conversation?

“Do you want to play?” is one of the most exciting and scary questions one can ask of another. The

vulnerability of the question opens the asker to possibilities of both profound rejection and deep

connection. In a play community, as theorized by Bernard De Koven (2013), the ethos of inclusion

dominates the ethos of the rule system. Whereas a game may remain rigid, ejecting the less masterful

players in favor of the most facile, the interaction of play is flexible when inclusion is centered

by bending and stretching to keep the players in play, together. In play, we carve out a space in

but apart from everyday life, where we may open ourselves to very real experiences of joy,

transgression, humor, and co-creation. Dominant modes of education are often un-playful.

With this notion of the seriousness of play in mind, instead of a misunderstanding of play as

frivolity or infantile, we have developed Feminist Philosophical Toys. Toys, as opposed to rules,

are the companions of play. While rules bound the scope of the game, the toy extends play, inviting

us into the community of play, acting as our avatars, and providing the friction of physical

materiality to push against.

Once constructed, even the object of the toy is not the toy. Instead, the toy comes into being

through play and action. The toy is a performative form and in this sense does not exist outside of

being played with. This is something we know on a deep level about toys, and an idea that shows up

in popular culture representations of toys, such as the toy characters in the Pixar Toy Story

movie

series. The Pixar toys all long to be played with, and feel most alive when at play. It is ironic,

though, that the Pixar toys express this feeling of aliveness by playing dead. Feminist

Philosophical Toys (FPT) are active when in play, and not in a feigned state of necrosis. Indeed,

the living nature of the FPT toys is emphasized in the eighth toy, which focuses on the

more-than-human entanglements of the paper material used to construct the entire toy series.

Unlike industrially produced toys, our toys are made by hand in DIY fashion, by the players. The

toys are created with humble materials (paper) and presented as a series of template instructions

that makers are encouraged to iterate, push against, and play with. The flexibility and ubiquity of

paper is a major affordance of the toys, and playful subversion of the academic paper. The intense

personalization of the toys resists commodification, and pushes back against dominant and often

damaging notions in design of universal user types or imagined personas. The generalizable is

replaced by the particular, emphasizing individuality but within the frame of community, as the toys

are intended to be made and played with in conversation with others. The fragility of the paper toy

suggests a limited temporality, shifting focus to the process of the toy making as opposed to the

generation of a durable end product. If the philosophical toy of the 19th-century illustrated

optical principles through interaction, the feminist philosophical toy creates philosophies and

paper artefacts through conversation among people with concrete histories, memories, ideals and

desires, who are bound by time and place.

In action, the FPT toys mediate conversations and imagination, working as companions that can help

decolonize educational contexts and disciplines by acknowledging the body, emotion, spirituality,

experience, and materiality as epistemology makers, de-centering the book/text. Semiotically, text

is a sign, whereas the toy is indexical, bearing traces of the maker. This stands in contrast with

the mainstream academic text, which if performed ”correctly” or in accordance with dominant values

in the Western academic tradition, is designed to erase all indices of the writer. This practice of

authorial erasure can be connected to fantasies of objectivity and logics of whiteness, that through

dominance seek a carefully constructed, normalized invisibility that is maintained by the often

violent marking of others.

The toys have been piloted both in the US and in Sweden with a range of ages from high school

through college, also with adult learners, and in disciplines including HCI, Game Design, Art, and

Education. For three of our toys, we present examples of what one of our students made as an

illustrative showcase. We note that the personal and cultural background of students as well as the

class environment and facilitation are key in shaping the character and quality of conversations

around the toys.

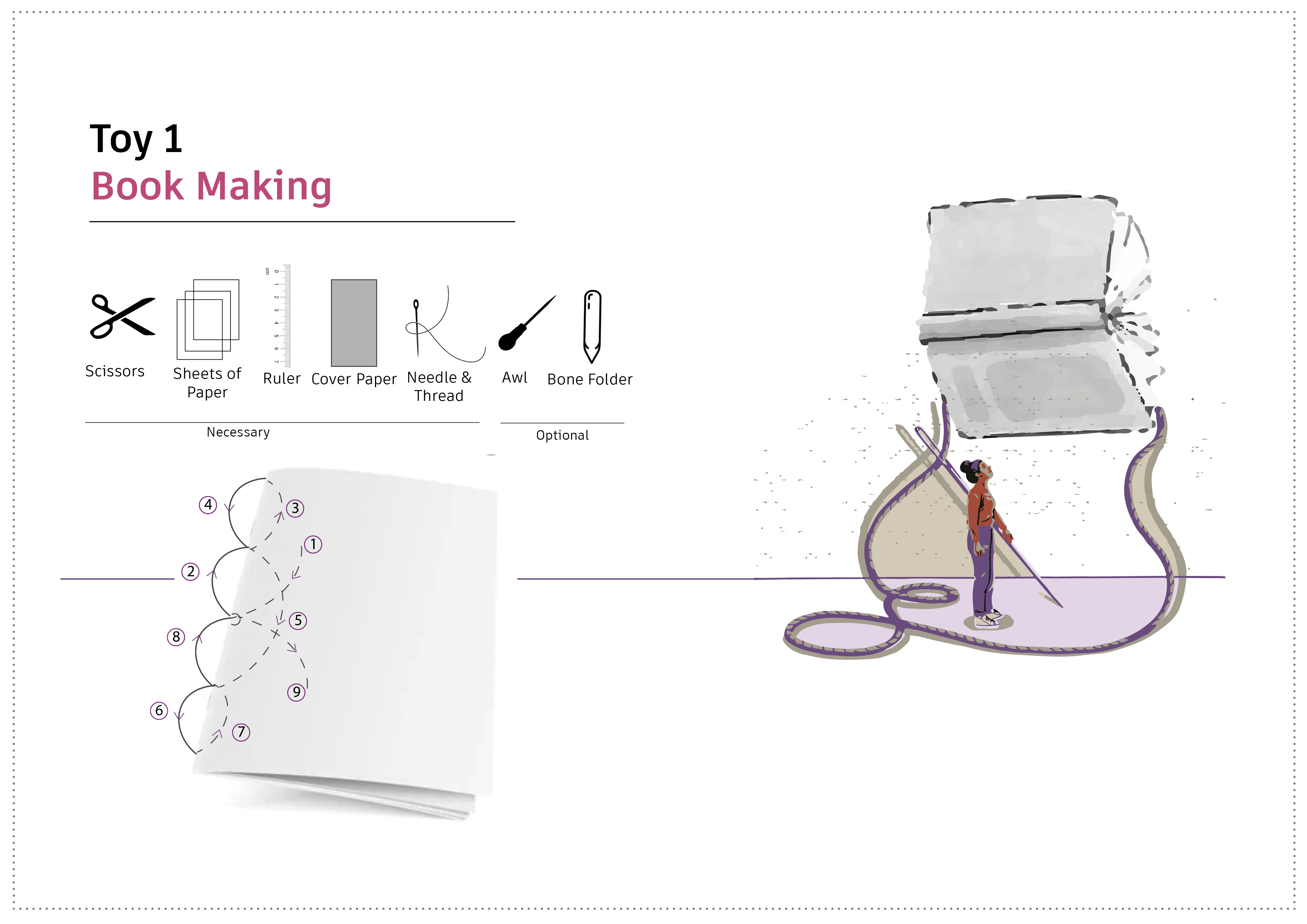

The series begins with making a handmade booklet with a sewn binding. Participants are introduced to the basics of bookmaking, which also provides them with a surface for keeping notes, sketches, or other materials used in developing the subsequent toys in the series, perhaps in collaboration with others. A basic set of materials are needed: interior pages, cover paper, needle and thread. The toy brings to the fore issues of knowledge production and showcases the rhetorical power of form and material mattering: once ideas are in a book, they are ‘present’ in a way that has a particular valence. This is an invitation for a collective conversation about knowledge making in different cultures and communities, and in academia too. In tandem with the making of Toy #1, related scholarship on feminist approaches to the book may be discussed including: Johanna Drucker’s The Century of Artists’ Books (2004); Jessica Helfand’s Scrapbooks: An American History (2008); Elizabeth Groeneveld’s Making Feminist Media (2016); Maryam Fanni, Matilda Flodmark, and Sara Kaaman’s Natural Enemies of Books: A Messy History of Women in Printing and Typography (2020); and Max Liborion’s Exchanging (2020).

Figure 1. Instructions for Toy 1: Book Making (Image Credit: Simin Nasiri)

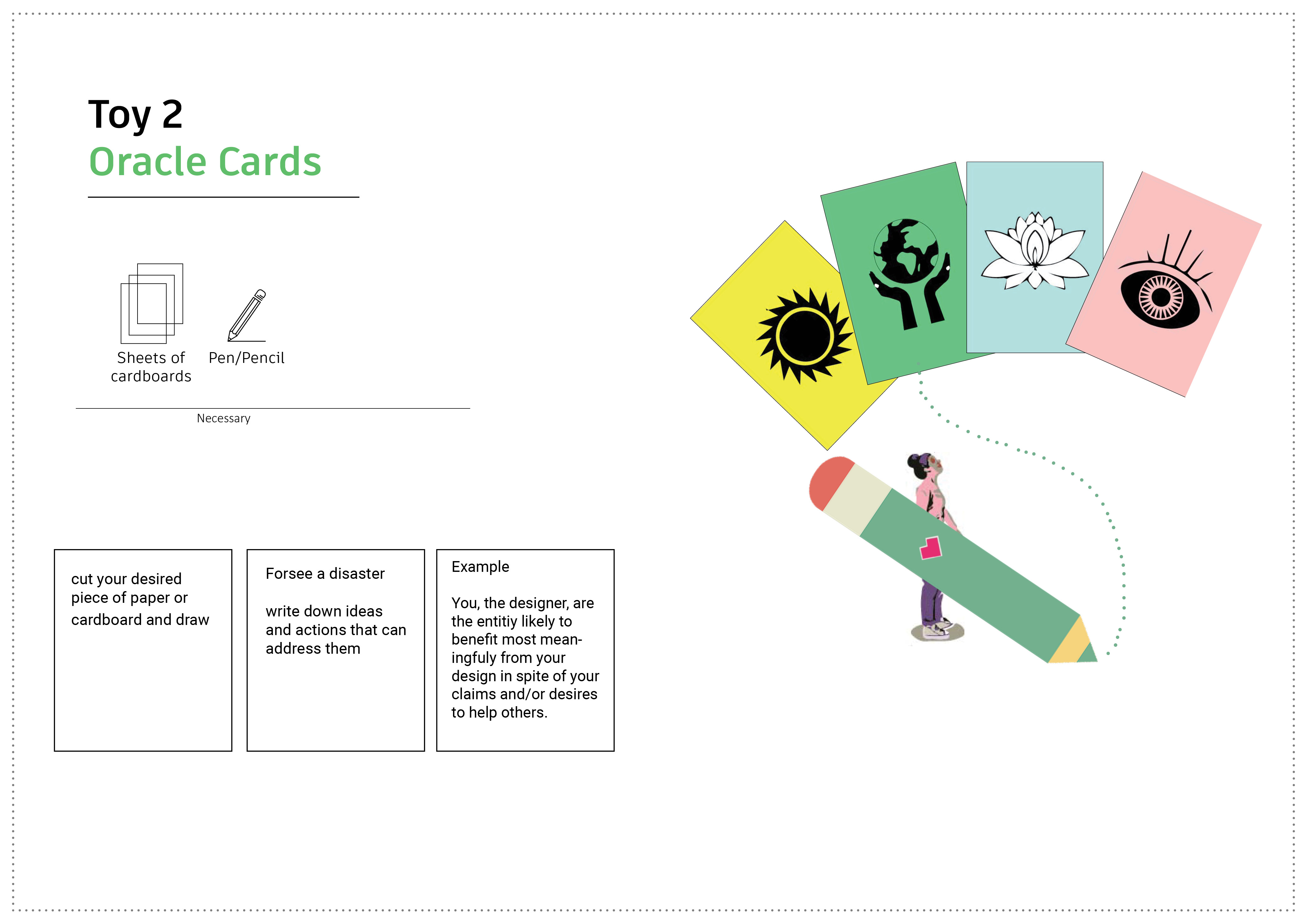

The second toy in our series, Oracle Cards, are a satirical play on the proliferation of design cards commonly used in much of mainstream vocational design education and industry, and offer a critique of the ritual of design short-cuts. These mainstream cards are designed as quick toolkits/checklists that designers may use to inform their practice. Indeed, coming from our shared context in design education, this toy was where our project began. This toy is offered as an ironic aid the designer who lacks foresight, who can benefit from the use of divination cards similar to tarot or other oracle decks in casting their imagination into the future but through the agential practice of designing the cards oneself. In doing so, it is meant to help the player foreground seemingly obvious issues, challenges, or frustrations that remain unaddressed nonetheless. Indeed, many artists have been inspired by the tarot form, not only creating artist tarot decks but also engaging the tarot across other forms such as literature, sculpture, and even fashion (Bradley 2022). Contemporary card decks outside design and games education include The Antiracist Deck developed by Kendi (2022) and the decks that are part of Terresa Moses’ Racism Untaught tool kit (2022, p. 149). These card sets play with form and the process of play, working to address serious issues of racism in society more broadly.

Figure 2. Instructions for Toy 2: Oracle Cards (Image Credit: Simin Nasiri)

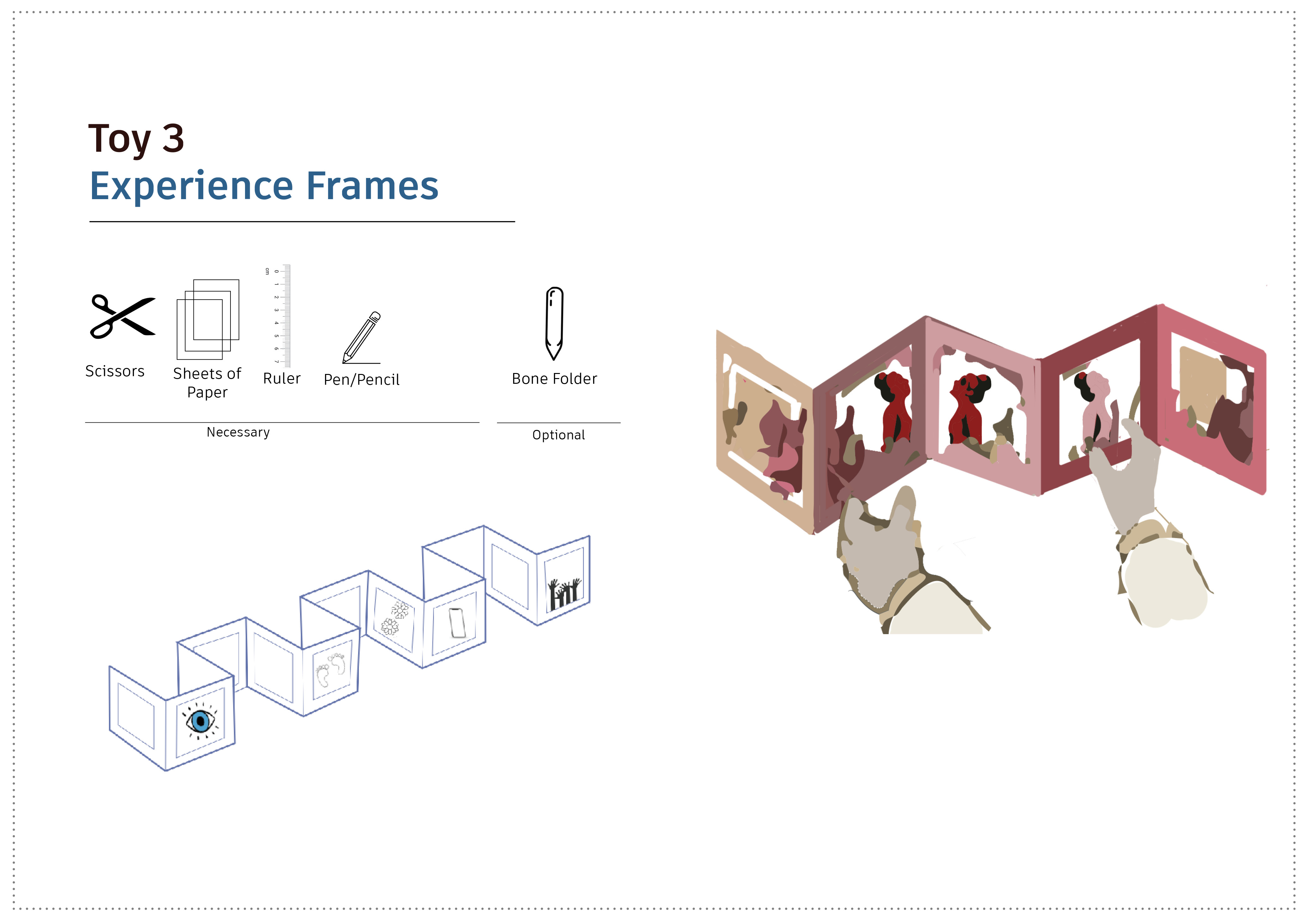

The third toy in the series which we refer to as Experience Frames centers that which defies expression, foregrounding on our experiences as they relate to specificities of our positions and histories (as opposed to essentializing categories of identity). Experience frames works to explore the concept of positionality both in knowledge-making practices and broader experiences of oppression (Harding 1990, Crenshaw 1990, Takacs 2003). The toy takes inspiration from 19th century movable books, such as die-cut accordion books by Lothar Meggendorfer. The form of the toy aims to surface and challenge reductive readings of intersectionality as an additive and stable notion of identity (e.g., race, sex, ability) and instead highlight the simultaneity and variety of experiences of oppression (e.g., racism, sexism, ableism) within everyday encounters. Through the making of this toy, we seek to draw out the idea of the oppressors within each of us no matter our location with this toy. In doing so, we invite participants to critically engage the history of intersectionality and explore both the pains and joys of centers and margins.

Figure 3. Instructions for Toy 3: Experience Frames (Image Credit: Simin Nasiri)

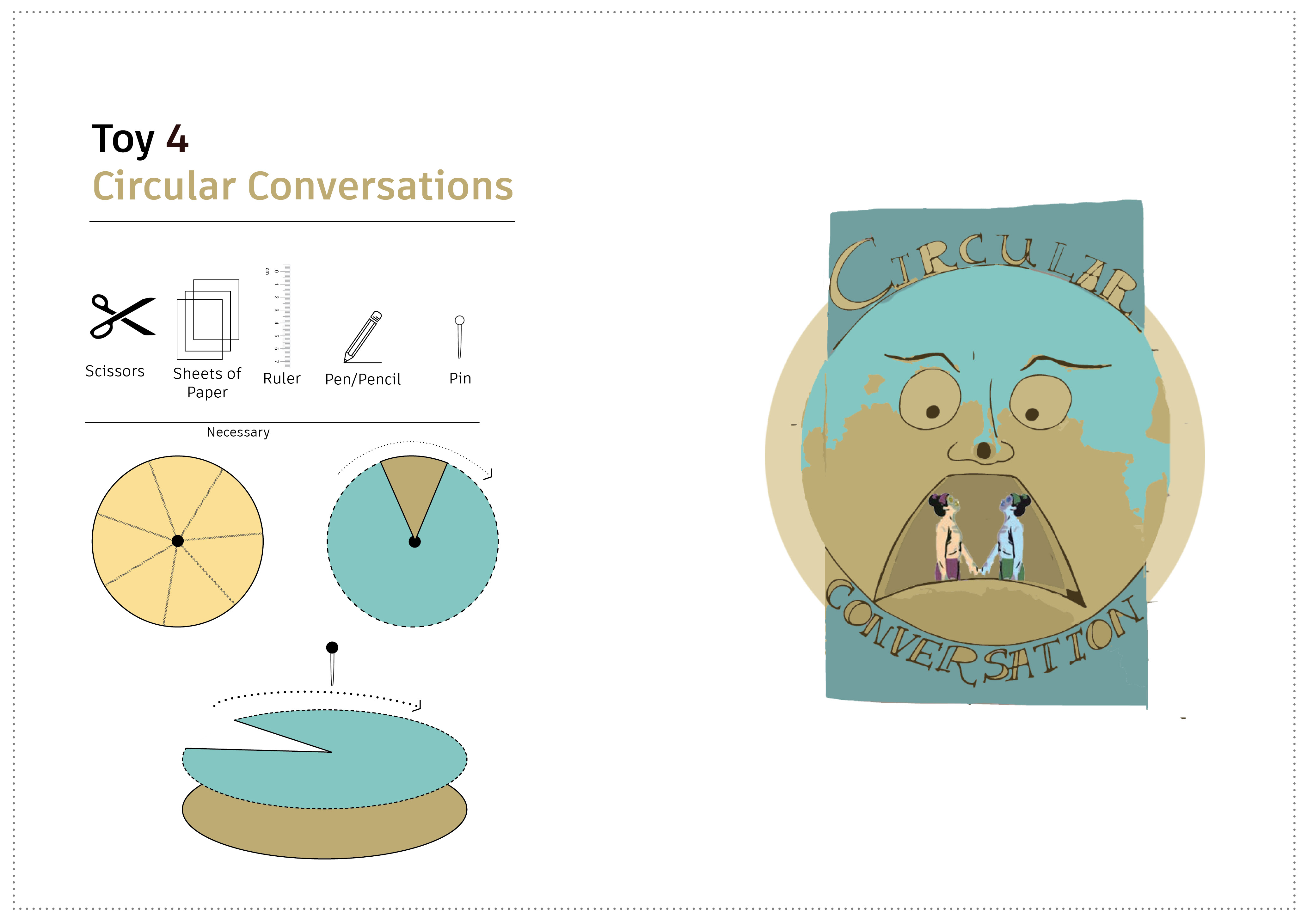

Circular Conversations is our fourth toy, focused on feminist scholarship that foregrounds the circularity of struggle, structures that maintain the status quo, and possibilities for breaking free from those oppressive cycles. The theory that animates this toy is in part captured in the concept of “Complaint as Feminist Pedagogy” as described by Sara Ahmed. The idea that we learn about “conditions of social membership” as we challenge them and/or try to break free from them. The power of the larger social group comes to fore, in part, through the illogical/circular nature of conversations we have with those that hold authority. More broadly, this toy aims to advance the liberatory potentials of performative practice (Boal 2006), and scholarship on the cyclic natures of both socialization and liberation (Harro 2018).

Inspiration for the toy is drawn from medieval volvelles as well as more contemporary 20th century "circle charts." Some of the earliest volvelles appeared in medieval books and were used for calendar or other astrological calculations. This volvelle is for expressing a circular conversation (the flip side of which is a rant) to aid in pinning it down, with the possibility to change, or let go of it. The volvelle mechanism is simple and interchangeable, multiple circular discs can be made and switched out to allow for the materialization and exploration of different circular conversations. Each comes with its own set of instructions for use.

For example, one circular conversation reads: Have an unsatisfyingly circular conversation with an elder for 20 years or more on the topic of one of their most deeply held prejudices that intersects with one aspect of your social identity. Maintain compassion for your elder. Maintain your sense of self-worth.

Be Reasonable!

Just don’t throw it in my face!

Are you sure? How can you know?

As Long as you’re not too pushy about it …

The theme of dialogue and idea of participatory thought connects this toy to the one that follows foregrounding conflicts and coalitions, issues and resolutions, problems and possibilities–both the overall messiness and unpredictability of conversations as well as their potentials and possibilities.

Figure 4. Instructions for Toy 4: Circular Conversations (Image Credit: Simin Nasiri)

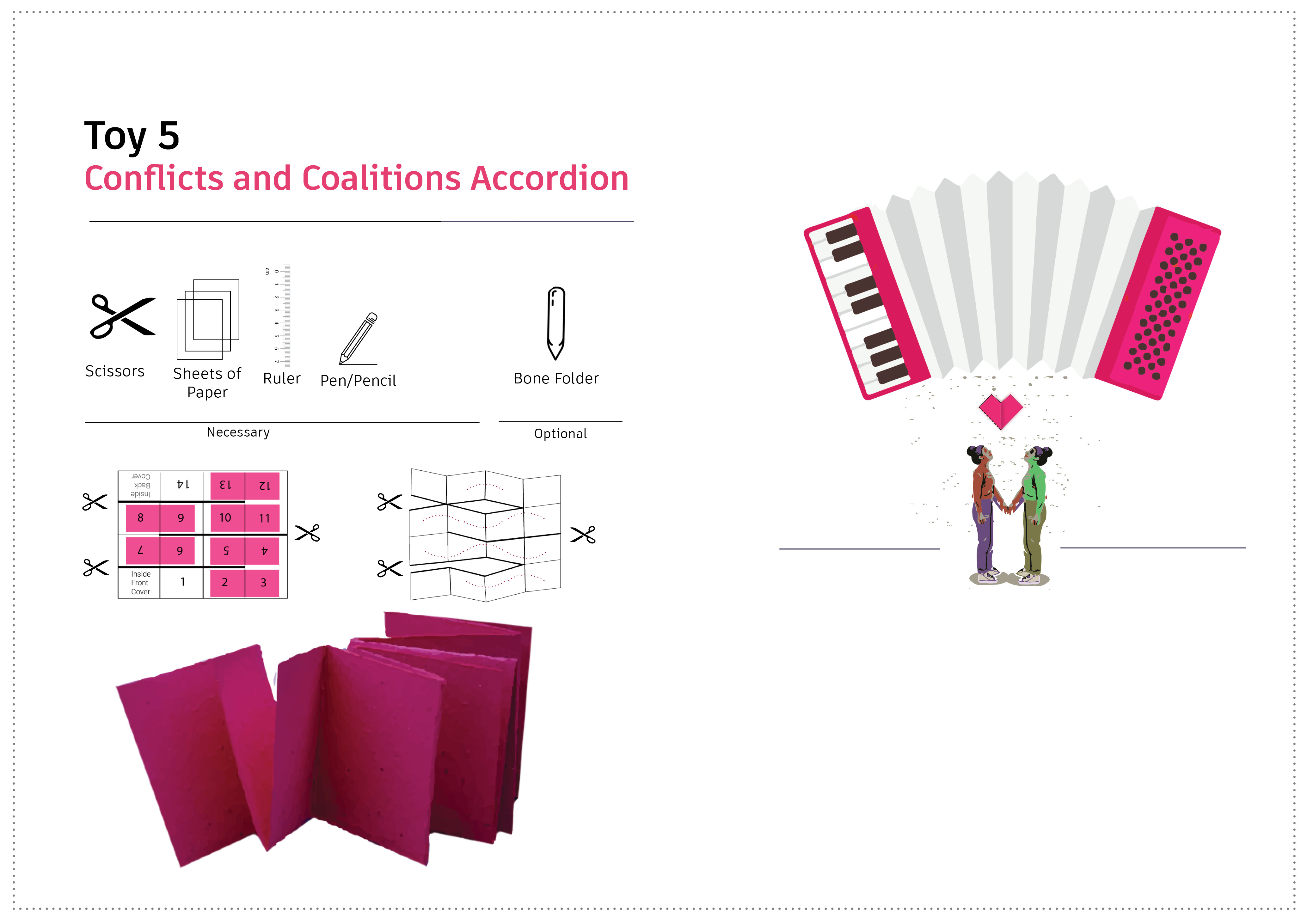

This toy takes its starting point in feminist scholarship on incommensurability, agonism, and the value of opposition and conflict as found in the works of Chantal Mouffe (2013), bell hooks (2010), and Susan R. Jones (2008). Differences and conflicts are surfaced and shared while at the same time possibilities for gathering (in spite of, because of, or by resolution of conflict and difference).

This toy takes the form of an accordion fold book, constructed from a single sheet of paper, in which each of the four sections of the book is positioned at right angles with another. Through the form of the toy, we seek to acknowledge and embrace conflicts and disagreements but also to encourage reflection on ways that we might find places of agreement or common courses of action. The toy captures moments of divergence and convergence as an ongoing dialectic. In doing so, the toy seeks to help identify and surface differences while at the same time underline the need for coalition building, collaboration, and collective action. Each participant is invited to first create their own single accordion, then work with others to cut up and reconfigure sections in new ways.

This folded book form resonates with the concept of agonism on an etymological level. To be in accord is to agree with. The name of the musical instrument, the accordion, likewise references the concept of being in tune, which here we can understand as being “in tune” with or in harmony with another’s perspectives or positioning.

Figure 5. Instructions for Toy 5: Conflicts and Coalitions Accordions (Image Credit: Simin Nasiri)

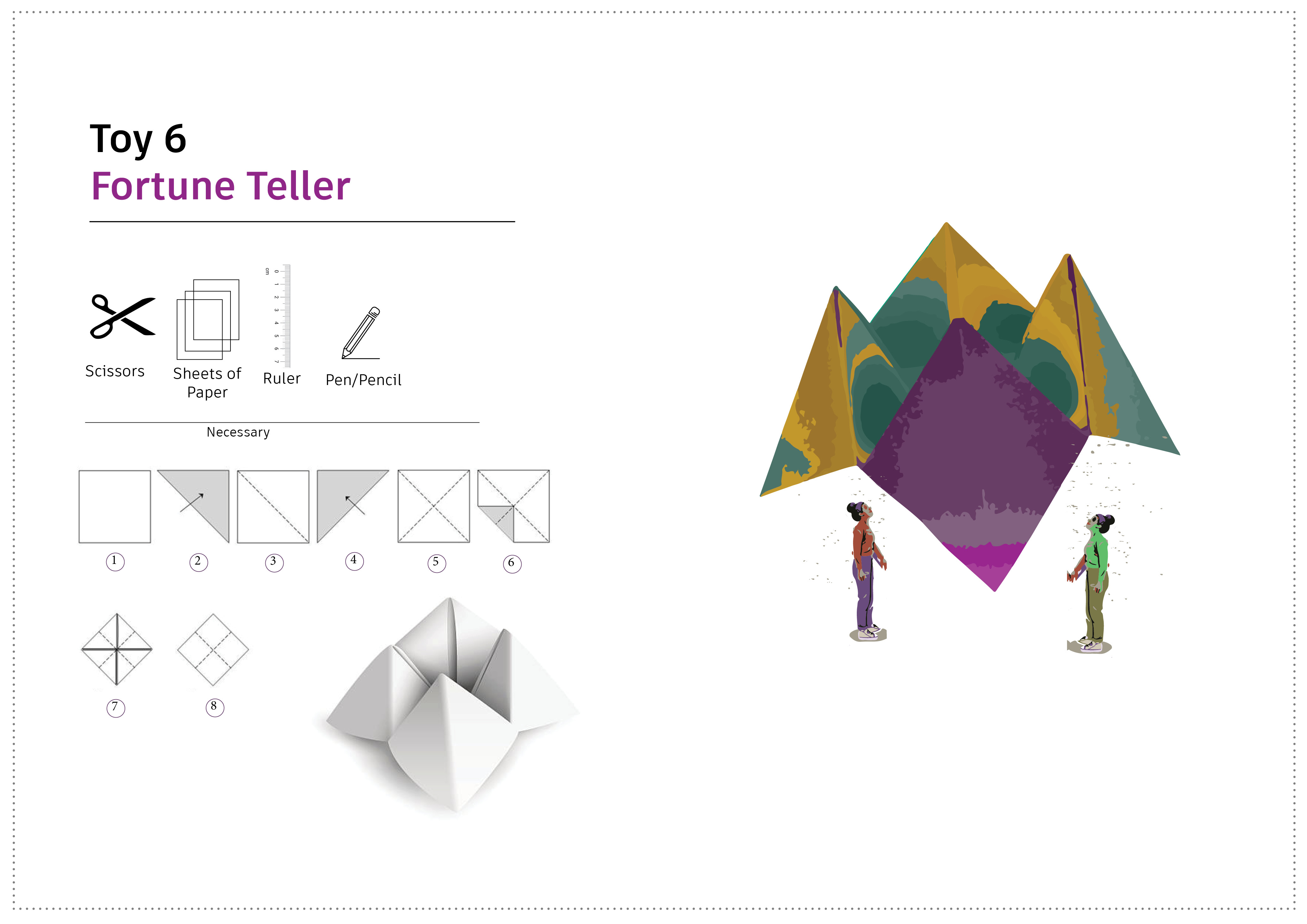

The sixth toy draws on the classic children's origami structure known as a fortune teller or salt cellar (Murray and Rigney 1928). This toy utilizes scale to change the nature of the interaction with the material form, scaling the fortune teller up to a larger size such that it can only be operated in collaboration with two or more people, and cannot be used alone. Recalling the use of the toy by school children to tell the future about romantic love, the form of the fortune teller helps connect this toy to the theme of love in a broader sense. In doing so, it helps problematize and contextualize that usage while reimagining it at the same time. The oversized form of the toy hints at something that is greater than each of us and beyond our individual reach or control. At the same time the collaborative part helps emphasize how we may each participate in our individual and collective becoming. The collaborative nature of the oversized form is also used to develop the content for the fortune "flaps," which display co-authored and/or co-illustrated representations of speculative futures. Participants develop this toy in conversation with work on feminism and futurism (e.g., Grosz 2000), feminist speculative design (e.g., Martins 2014), and feminist theories of fiction and storytelling (e.g., LeGuin 2019).

Figure 6. Instructions for Toy 6: Fortune Teller (Image Credit: Simin Nasiri)

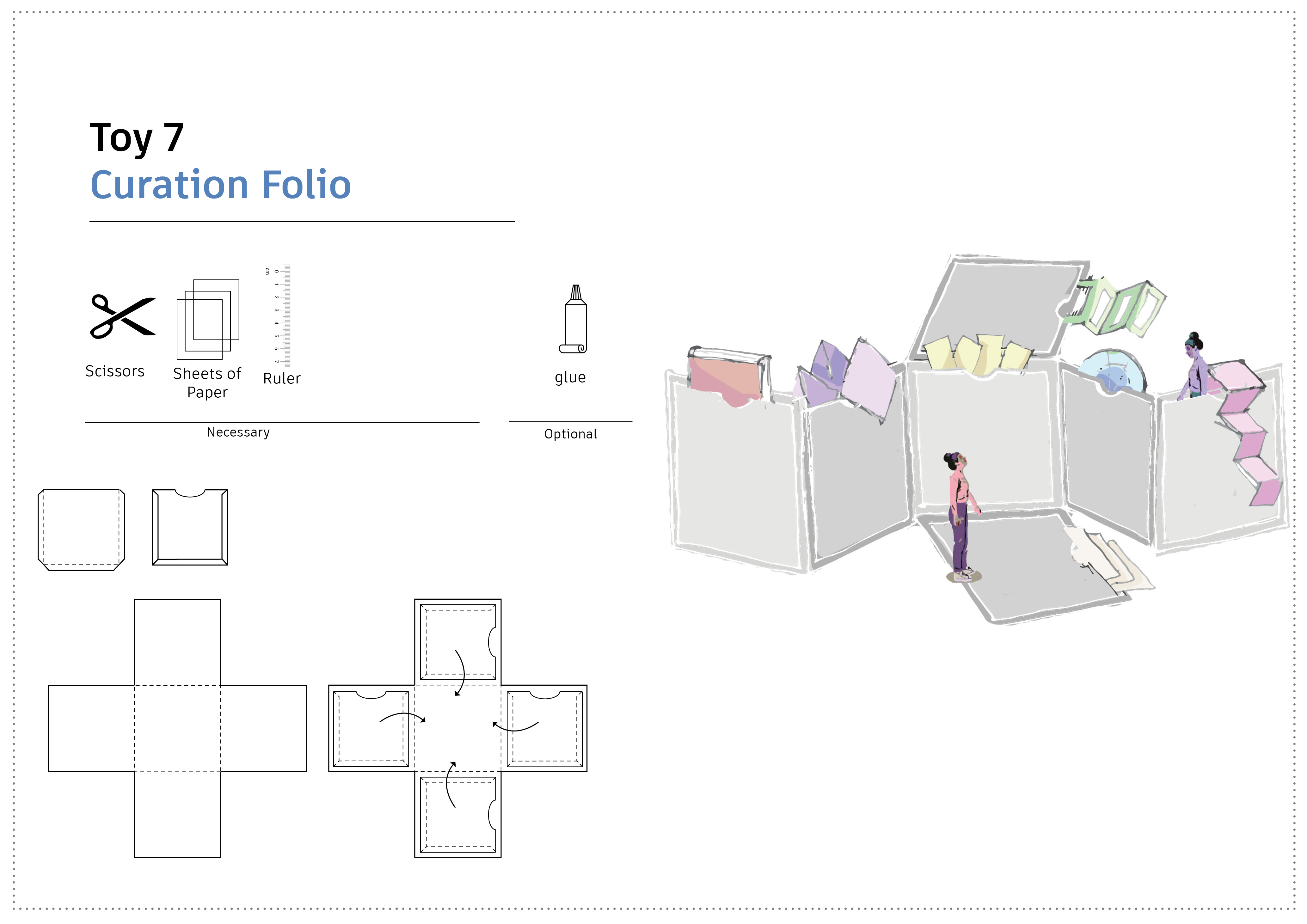

This is a paper folio with pockets for bringing the other toys together into an assemblage. The framing and arrangement of the structures that hold and therefore also produce knowledge are discussed, in relation to Karen Barad’s work on agential cuts (2007). In discussing the kaleidoscopic potentials of the cut, Barad relates the story of the slit/scan experiment in physics, in which different designs of the system used to discern the nature of the atom function to constitute the nature of the atom itself in different ways. Related to this, feminist scholarship from informatics is included, such as Bonnie Mak and Julia Pollock’s research on the history and power relations of the card catalogue (2020).

This toy also draws on perspectives on feminist curation in the art world (Dorothee Richter, Elke Krasny, and Lara Perry 2016). In this collection, Dorothee Richter in particular addresses feminist issues relevant to curation, and a discussion of curatorial strategies to resist the traditional patriarchal structures of many curation spaces. The foundation of Richter’s argument is the notion that: “Curating is a form of knowledge production which means, it is also a gendered form of knowledge production” (Richter 2016: 62). In spite of the theme of collecting in curation, the seventh toy is discussed not as an ending or culmination, but rather a beginning. Participants are encouraged to bring their work in relation with each other in new ways that may also be shared with a wider public, such as through publication of zines as discussed by Groeneveld (2006).

Figure 7. Instructions for Toy 7: Curation and Collection Folio (Image Credit: Sylvia Janicki)

What is the philosophy of paper, itself, as a living material which we live with and through? The living toy engages with the philosophy of paper via Blasche’s idea that through the creative manipulation of paper “the principle of geometry become “anschaulich” (accessible to the imagination)” (Iurascu 2021, p. 210). In this sense, paper acts as a kind of revelatory or scrying medium for allowing us more transparent access to our most creative selves.

Here we see ideas about how the seeming simplicity of paper is countered by its flexibility, allowing it to operate as “nothing” and “everything” at the same time. Paper is a transparent or invisible medium connecting us to imagination. It is also the “equivalent of the complex world,” as solid, representational, formalized paper object, helping us to grasp complexity through its grip. Paper is accessible and disposable but can also be made to last. In this way, we think of paper as humble material, one that goes against fetishization of matter in some art and design practices through the use of precious materials that require a lot of expertise or that cannot be touched, felt, or manipulated.

From these perspectives, we are invited to understand paper in its connection to living matter (the tree, in the case of paper made from wood pulp), and the complex entanglement of industrial, ecological and cultural processes that produce, circulate, and transform paper.

Figure 8. Instructions for Toy 8: The Living Toy (Image Credit: Sylvia Janicki)

While the toys are easy to make and engage, we don’t see them as standalone pedagogical artifacts.

To the contrary, it is crucial for the facilitators/educators to create a “brave” space as theorized

by Brian Arao and Kristi Clemens (2013) in the learning environment in which students (and

instructors) are invited to bring their whole selves into relation with each other and the material.

This is only possible when the group has attended to shared concerns around how we communicate with

each other and developed a shared understanding of the purview and goals of the educational

experience as co-created between learners and instructors. The toys are intended to help surface

what matters in the situation, and we expect that in the development of conversation, participants

push against, amend, adjust, and reinvent the materials too. The juxtaposition of philosophical and

playful in “philosophical toys” is intentional to make philosophy grounded and accessible. Toys can

be played with and kept. You can grow with toys and find them an object of lifelong learning and

fascination. But you may also outgrow toys (and theories, too). Ultimately, it is the knowing

through meaningful exchange in embodied dialogue with others, materials, and the communities and

connections we build in the process that have the potential for radical transformation.

Feminist Philosophic Toys is an ongoing collaborative project by Rebecca Rouse (University of Skövde,

Sweden) and Nassim Parvin (Georgia

Tech, USA).

For information about how to use the toys in the classroom, please contact nassim [at]

gatech.edu and/or rebecca.rouse [at] his.se